14 - #JustAsk

(Want to listen to this post instead? Less screen time! For audio, click here)

In June, I went to an improv conference in Toronto. I’ve been doing improv for about four and a half years now and I started officially teaching at the beginning of this year. Not only was this improv conference the first I have gone to, but it was also the first time I was capable of traveling to another city for improv since my injury. My fellow improvisers, with whom I’ve been practicing and performing the last four and a half years, had already gone to a number of other cities for festivals, workshops and intensive courses.

In my city, my improv community has been very good to me, including me and making accommodations when possible. But the brain injury has still limited my opportunities in comparison. As a result, I have often felt left out. Even though I am a member of the community, it can feel like I am not truly a part of it. For this reason, the conference in Toronto was more than just a milestone in my recovery. It was an opportunity to truly connect with my community and to feel a part of a purpose larger than myself. The theme of the conference was also perfect for me at this point in my journey. The focus was on how to make the improv scene in your city more safe, diverse, inclusive and accommodating for people in under-represented populations.

The conference was insightful, mind opening, practical and, well, dense. It’s not an easy topic. You can’t talk about creating safer and more inclusive spaces for marginalized populations without unpacking your own privilege. I admit, I may be marginalized as a woman with a disability and mental health issues, but I’m also white, heteronormative and have thin body type privilege. It’s a hard thing, coming to accept that we have advantages in life over others; that we have prejudices and biases. This doesn’t make us bad people though. When we start to unpack all this, our knee jerk reaction can be to defend ourselves - to try and prove that we’re one of the good ones…we try to protect ourselves from feeling shame. This reaction, however, takes focus away from the real issues; the stigma, barriers and struggles others are born into and faced with day-to-day. I think the more we come to understand this, the more we can support the quality of life of different people with different needs and therefore improve the overall well-being in all of our communities. After all, the accommodations made for me that were mutually beneficial for me and my improv peers haven’t been limiting to the larger group, and I’ve been able to contribute a lot to this same community. I do believe that working towards inclusion and accessibility as a norm is a win-win-win-win-win for all involved.

At the conference, there was representation from many different groups: people of colour, LGBTQ+, older age adults, people with mental health illness as well as visible and invisible disabilities. In fact, I was not the only attendee living with a brain injury. I had a wonderful conversation with a wonderful improviser who has an acquired brain injury due to a chronic illness. Also, they use a motorized chair. Their particular improv theatre had never before accommodated a student who used a mobility device. It was a steep learning curve and there is still more to be done. But this person became the first improviser to graduate the program using a motorized chair in class and on stage.

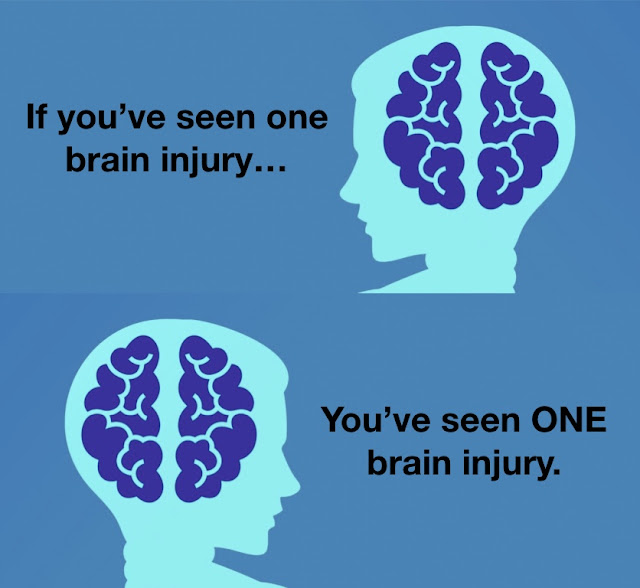

This improviser and I talked, of course, about how much we love improv (we may have different abilities, but we’re still improv nerds!). We talked about how much improv has helped us in our journeys. We also talked about how we’re glad to advocate for others with disabilities, but how we don’t want to be seen as THE example for everyone. We agreed that what has worked for us, the lengths we are willing to go, the not-so-perfect accommodations we are willing to deal with and the way we interact with our environments should not be expected for another person with the same issues. Even if someone shares our exact same diagnosis, their abilities, needs and symptoms can be totally different.

We are not the poster children of disabilities.

I am not the only face of brain injury.

One of the goals of this blog is to share my experiences living with PCS in the hopes that it helps others better understand the issues around brain injury. My blog posts have revealed larger themes that could be applied to many people’s lives, brain injury or not. But when it comes to my specific issues, my unique struggles, my particular symptoms, I ask that no one take my experience as the standard for all brain injuries. Another person who has hit their head in the exact same way and with the exact same force may have completely different issues, struggles and symptoms - they may need completely different accommodations. When I talk to others with PCS, I sometimes find that activities and stimuli that one person can tolerate may be absolutely intolerable to another. For these reasons, in this blog I try to stay away from talking about specific modifications or therapies that I or others have found helpful. Or, at the very least, I try to note that what is pleasant for me may be dreadful for another. There truly is no standard when it comes to brain injury.

At the improv conference, one of the final exercises we did was to brainstorm ways we could modify certain improv games. The improv games discussed usually require people to be standing, making eye contact, focusing on quick gestures and moving the whole body. We considered adjustments or other games that could maintain the key purpose of the improv exercise, while being accessible for people with hyperactivity, vision impairment, difficulty with social cues, mobility devices and difficulty hearing. The list of modifications we came up with wasn’t nearly as important as the thought process itself. It was a great exercise in imagination; practicing going beyond the typical limits of such improv games. But what I found most important was that during the process of trying to figure out what would be best for people with different abilities, there was the resounding realization that we can’t figure out or assume we know what’s best. To make these games truly accessible, what we have to do is ask.

The wonderful improviser with the acquired brain injury and the motorized chair shared how one of their teachers initiated a 20-minute phone conversation before the start of their improv course. The teacher aimed to learn what was ok, what was not; what barriers existed, what can help; and finally, what that student improviser was ok sharing with the other students and how they’d prefer their unique abilities be addressed. I don’t think the teacher expected this student to have all the answers. The teacher didn’t leave it up to the student to get everything they needed - I don’t think it’s fair to put all the responsibility of change for inclusion on the people who need it. Instead, the teacher admitted their limited experience, collaborated with the student and shared the responsibility for making it work. And all it took to get started was a 20-minute phone call that likely saved that teacher a lot of time throughout the course. The space was made safer for that improviser, even before the first class. In the conference, this check-in approach was designated the hashtag: #JustAsk.

I think at the end of the day (and correct me if I’m wrong), regardless of health and brain status, no one wants others to assume what’s best for them. Everyone wants to be respected, be heard and feel connected within all of their communities. By the same token, everyone has a right to their privacy and no one needs to share their personal trauma with just anyone. Part of respecting, listening to and connecting with others is honouring their boundaries. #JustAsk does not give us the right to ask any stranger about the most difficult part of their life, nor does it mean we should insist that people with challenges help us understand their struggles and take our support.

I really do appreciate when people want to learn more about my life with PCS. I do welcome offers of help at a time when I can feel completely helpless. But I also appreciate when people ask my permission before questioning me about my brain injury - I don’t always want or need to share my story. Sometimes people have offered me help, incorrectly assuming they know what I need, making their help unhelpful. #JustAsk therefore also means asking for permission to talk about the issue and asking if the help we can offer is supportive. Ultimately, it is about listening to and acting with compassion for all people in our communities.

I’m happy to be doing this blog. I’m glad I can give insight into the world of living with PCS for those who have never experienced it (and hopefully never will). I’m happy to help people with PCS feel less alone in their experiences as surely there are many things here we can all relate to. But based on my blog alone, we cannot assume that what I personally can and can’t do, need or don’t need and what works and does not work for me is true for all people with PCS. I am not the poster child of brain injury - no one is.

If you’ve seen one brain injury, then you’ve truly only seen one brain injury. To better understand the personal struggles of a person with a brain injury in your community, or to help them overcome their unique barriers if they are in need, use this blog as supportive information. But the best thing to do, with genuine respect, curiosity and permission, is to #JustAsk.

From me to you, all the best in brain health,

From me to you, all the best in brain health,

- Krystal

Find this post interesting? Feel free to share it or leave a comment! You can also message me using the message box in the sidebar or by email at this.hat.is.a.helmet@gmail.com. Cheers and happy brain health!

Wonderful post Krystal! And yes, we should all #JustAsk.

ReplyDelete